|

This trunk was originally owned by John Cameron, also known as John Cameron the Rich or Squire Cameron. The trunk is made of seal skin and the label on one side reads, “John Cameron Esq. Fairfield, Lancaster.” The destination “Lancaster” on the label can be explained by the fact that travel in the early 1800s (pre-railway days) was usually by boat. If John was travelling from Toronto, he would have directed the trunk to the closest wharf to his home, Lancaster.

John the Rich’s father, John Cameron the Wise came to the Province of New York in 1773 onPearl. He settled with his family on Sir William Johnson’s land in the Johnstown. John Cameron the Wise and his family moved to Glengarry with Sir John Johnson and settled on the Western half of Lot 17, Concession 1. He named this land Fairfield. John Cameron the Rich inherited this land that was just West of Summerstown. John the Rich joined the Glengarry militia in 1803 and became a Lieutenant during the war of 1812. He served the First Glengarry Flank Company through the war and was Member of the Legislative Assembly for Glengarry County from 1816-1820. He later married Elizabeth Summers of the Summerstown family. At the time of John the Rich’s death, he left over 3800 acres in his will. Please note this trunk did not belong to John “Cariboo” Cameron. John Cameron the Rich was related to “Cariboo” who later bought the land called Fairfield. 1991.007.001 References “Dictionary of Glengarry Biography,” Royce MacGillivray, 2010. originally published on norwestersandloyalistmuseum.ca on September 12th 2013

3 Comments

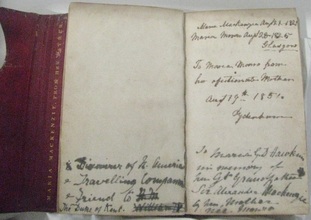

John A. Cameron, better known as “Cariboo Cameron”, was born September 1st, 1820 in Charlottenburgh Township to parents Angus Cameron and Isabella McDougal. In the 1850’s, Cameron was in California working as a gold prospector. Soon later, he returned to Glengarry County before making his way to the Cariboo in British Columbia, with his wife Margaret, to mine for gold. During this time, he also began a business association with Robert Stevenson. Cameron wasn’t in Cariboo long when, in December of 1862, his miners struck gold in the Cameron Claim, which made Cameron a very wealthy man. Sadly, only a few days prior, his wife Margaret had passed away of mountain fever. Although the fortune Cameron earned after striking gold was undoubtedly remarkable, it was the promise he kept to his late wife that made him famous. Margaret had asked to be buried in her home town of Cornwall, Ontario, and Cameron went to great lengths to assure that her wish be granted. She was buried for the first time in a tin casket beneath a deserted cabin and soon after, in January of 1863, Cameron and Stevenson dug up her casket and made their way 1000 kilometres West to Victoria, B.C. They travelled by snowshoe, horse, and steamer. Upon their arrival in Victoria on March 7th, they buried Margaret for a second time. A few months later, in November, they dug up her coffin once again and made their way to Ontario. Finally, shortly after Christmas in 1863, Margaret received her third and final funeral in Cornwall. In order to preserve her body during this lengthy voyage, her coffin was filled with alcohol. There is controversy surrounding the entire story. There are rumours that state that her coffin was actually filled with gold instead of her body. Another rumour accuses Cameron of having sold his wife to an Aboriginal chief for gold and Margaret had not died at the time Cameron claimed. After Margaret’s burial, Cameron decided to settle in Glengarry and built the costly and splendid Fairfield House at Summerstown. However, Cameron’s triumphs did not last and he eventually lost his fortune. Cameron died at Barkerville, B.C., near the gold mine that made him his fortune, and was buried at Camerontown; which was named after him. Standing: (From left to right) Robert Stevenson, Sam Montgomery Sitting: (From left to right) Allan, John (Cariboo) and Roderick Cameron This photograph as well as the frame were graciously donated to the Nor’westers and Loyalist Museum by Katherine McLellan, in 1968. The frame is ornate gilt gesso with four flowers and medallion motifs. 1968.001.001 “Dictionary of Glengarry Biography,” Rocye MacGillivray, 2010 Dictionary of Canadian Biography http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/cameron_john_1820_88_11E.html originally published on norwestersandloyalistmuseum.ca on August 30th 2013  Sir Alexander Mackenzie was born at Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, Scotland in 1764. Mackenzie’s father Kenneth and his uncle John made their way to New York colony not long before the American Revolution began. During the war, they served as Loyalists in the King’s Royal Regiment of New York. Because of the war, Alexander was sent to Montreal in 1778. Shortly after, in 1779, he began to work in the fur trade. At first he was a clerk in a Montreal counting house, but he was soon sent out to work in the field as a trader. He worked for the XY company and then later the North West Company; where he was quite successful. Although he did well as a fur trader, he also had an interest in exploring. There a two primary explorations done by Mackenzie. The first is the 1789 Mackenzie River expedition to the Arctic Ocean. Mackenzie started his journey at Fort Chipewyan hoping to discover a navigable route that would lead to the Pacific Ocean. He did not end up finding the Northwest Passage to the Pacific Ocean, but rather the passage to the Arctic Ocean. Mackenzie was presumably very disappointed by this, seeing as he went on to name the river the “Disappointment River”; which was later renamed Mackenzie River. Mackenzie returned to Great Britain in 1791 in order to study longitude. Upon his return to North America in 1792, he began his second exploration; which had the same objective as the first: to reach the Pacific Ocean. He was accompanied by two aboriginal guides, his cousin Alexander MacKay, and six Canadian voyageurs. Leaving from the Peace River west of Fort Chipewyan, Mackenzie finally reached the Pacific coast. As far as it is known, he was the first European to cross North America coast to coast, North of Mexico. Mackenzie died March 12th, 1820 from Bright ’s disease. Sir Alexander Mackenzie had close ties with Glengarry. He had several family members who were residents of Glengarry County but he also had direct liaisons with the county. He contributed a bell to the Presbyterian Church at Williamstown, which is still in use to this day, and he also had a pew that was reserved for his use. This Bible may have once belonged to Alexander Mackenzie and was given to his natural daughter, Maria, who was born c.1806. Maria has been unaccounted for in the published history of Alexander Mackenzie, because of the lack of documentation and possibly her parentage. This Bible was passed down through generations as an heirloom. It was graciously donated to the Nor’Westers and Loyalist museum by Ken Hawkins in 1986. 1986.007.001 Sources: Dictionary of Glengarry Biography by Royce MacGillivray, 2010 originally published on norwestersandloyalistmuseum.ca on August 17th 2013 This flag is the King’s Colour, Second Battalion, Royal Canadian Volunteers flag which was raised in 1794 and disbanded in 1802. This is the first known flag to reference Canada as a political entity and to use the “Royal” designation in reference to a Canadian military regiment. This is most likely the oldest surviving flag in Canadian History. It is made of silk and is hand painted. There are also some repairs on it which are said to have been battle repairs due to damage possibly made by a musket or another weapon. This item is currently on display at the Nor’Westers and Loyalist Museum.

In 1794-1796, as tension rose between Canada and the United States, the British decided to form a regiment called the Royal Canadian Volunteers. The RCV were meant to serve exclusively within North America. Within the regiment there were two battalions: the first being a Francophone battalion lead by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph-Dominique-Emmanuel Le Moyne of Longueil, representing Lower Canada; the second being an Anglophone battalion led by Lieutenant-Colonel John MacDonell, representing Upper Canada. John MacDonell of Aberchalder was born in Scotland to parents Alexander MacDonell and Mary Macdonald. His father helped lead the emigration group on the Pearl in 1773 to New York. Upon their arrival in North America, the family settled on Sir William Johnson’s estate located in the Mohawk Valley. Shortly before the American Revolution, MacDonell had been working in Montreal at an accountant’s office. Once the Revolutionary War began, he made his way back from Montreal and on June 14, 1775, he began his prominent military career with the Royal Highland Emigrants as an ensign and later was promoted to lieutenant. Subsequently, he was transferred to Butler’s Rangers and whilst serving with them, became a captain. When the RCV was formed, MacDonell was chosen to command the Upper Canada battalion on recommendation from Lieutenant Governor Simcoe. Simcoe’s reasoning: MacDonell allegedly had a strong relationship with the Aboriginals at St-Regis, and was believed to have a great deal of influence on them. He was also a leader for the Gaelic-speaking Highlanders which assured that the Highlanders would support and follow him. MacDonell was in command of the 2nd battalion from 1796 to 1802, when it was disbanded. He retired afterwards to the residence he had built near Cornwall, as he enjoyed and preferred to live along the St Lawrence River among the Highlanders. He called this residence the “Glengarry House”. Lord Selkirk states that there was a certain resentment caused by MacDonell naming the house the “Glengarry House” because it implied that he was the leader to the MacDonell clan. After only a few years of retirement, financial insecurity forced him to re-join the military, but this time, he would work as paymaster to the 10th Royal Veteran Battalion stationed at Quebec. MacDonell was already of poor health and the cold Quebec climate likely proved to be too much for him. In November of 1809, he caught a severe cold and passed away just a few weeks later. A few short years after John’s death; the house caught fire and was destroyed during the War of 1812, but not by enemy action. The ruins, however, still remain to present day at what is known as Stone House Point. In his personal life, John was said to have been a prominent figure in early Glengarry County due to his wealth, family connections, powerful friends, military record, and most likely also due to his personal energy and character traits. He was married to Helen Yates and had three children together, one of whom was Alexander MacDonell: a major who served in the Glengarry militia during the suppression of the 1837-1839 Rebellion. 000.001.17 Sources: Dictionary of Glengarry Biography by Royce MacGillivray, 2010 Kings Royal Regiment of New York by Brigadier General Ernest A. Cruikshank, L.L.D., F.R.Hist.S. http://www.cmhg.gc.ca/cmh/page-356-eng.asp http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mcdonell_john_5E.html?revision_id=1740 originally posted on orwestersandloyalistuseum.ca on August 7th 2013  During the American Revolution, muskets, their attached bayonets, and cannons were the primary weapons supplied. The British Land Patterned muskets, nicknamed “Brown Bess”, were introduced in 1722 and produced into the 1860s. Other weapons were available such as rifles and pistols, but muskets were preferred because they were more convenient due to how quickly they could be fired. Generally, muskets could be fired approx. every fifteen seconds as opposed to rifles that required at least thirty seconds, or more, to reload. Rifles were much more accurate than muskets; it was nearly impossible to hit a target accurately from more than 75 yards away using a musket. Black powder was used to fire the lead bullet, however it leaves a residue in the barrel, affecting the bullets ability to travel in a straight line; this could be overcome by using larger bullets. In order to compensate for its lack of accuracy, the musket came equipped with a bayonet, which the rifle did not have, and proved to be useful in close combat. When using muskets, certain tactics needed to be employed in order for them to be effective. Typically, the soldiers would stand in a relatively straight line, shoulder to shoulder, and fire in unison to create a volleyed attack; this tactic gave a second line of soldiers time to reload. The premise of the musket was not necessarily to shoot down the enemy, but rather to break up a line of soldiers in order to push through them. Once the line broke, and they were in closer proximity, then the bayonets became very useful. There are several variations of the musket; however, the musket that is currently on display is an India Pattern Brown Bess musket. This particular variation was in service between 1797 and 1854 although some were in use prior to 1797. It is 139 centimetres long and its width varies between 5 centimetres and 11 centimetres at its widest point. It weighs approximately 10 pounds. It has a steel engraving of the British Crown near the trigger and just left of the crown the word “Tower” is engraved confirming that it is of British military pattern and was assembled at the armouries of the Tower of London. It is manufactured out of wood as well as metal and is still in very good condition. This musket has been in the family of Donald MacDonell since 1784. It is said to have been used in the battle of Culloden by Roderick Roy MacDonell who was the original owner. 2006.012.001 Sources: http://www.doublegv.com/ggv/battles/tactics.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brown_Bess#Variations originally posted to norwestersandloyalistmuseum.ca on August 1st 2013  The tombstone reads, “In memory of Thomas Ross of Lancaster, a native of Kincardine, Rosshire, Scotland, who died/departed this life the 22 July 1794, aged 78 years, and Isabella Ross his wife who departed this life the 24 Sept. 1817, aged 74 years. This stone is erected by their affectionate sons Donald, Alex., John and George Ross.” Thomas Ross was a United Empire Loyalist who served with the British Army at Quebec in 1759. Ross immigrated to America on the Pearl with his wife Isabella and his son Donald in 1773. He became a tenant of Sir William Johnson on the Kingsborough Patent in what is now New York. During the American Revolution, Thomas Ross fought with the King’s Royal Rifles of New York. When the fighting was over, Thomas was discharged in December of 1783 and moved north to Upper Canada with other Loyalists. As a Loyalist he was granted Lot 28 in the 1st Lancaster Township, which is a mile east of what is currently Lancaster. This tombstone made its way to the Nor’Westers and Loyalist Museum in 1988, after the descendants of Thomas Ross replaced his tombstone and his son’s, John Ross. Both tombstones have been in storage for several years, and this June it was decided both would go on display. Thomas’s tombstone is now in the northeast corner of the museum property, while John’s is inside on display in our “Wonders from our Attic” exhibit. John’s tombstone will join Thomas’s at the end of August. Dictionary of Glengarry Biography Royce MacGillivray, 2010 1988.017.001 originally posted to norwestersandloyalistmuseum.ca on June 25th 2013 |

AuthorHi everyone! My name is Keleigh and I'm the curator at the GNLM. Categories

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed